We do not like long test scenarios with loads of different asserts. A test case that has many expectations is difficult to understand when it fails. We then have to dig inside the test’s implementation to see what exactly went wrong where. Before we know it, we fall in to a lengthy debugging session.

Our guideline is that a test should have one (and only one) reason to fail. Per test we have a single assert or expectation. Sometimes it is more convenient to have a few asserts, e.g. asserting multiple properties of the same thing. We tend to regard this as conceptually one assert.

Example - And, and, and

Let’s look at an example in Java, from an order processing application.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public void savesOrderAndNotifiesOwnerIfPaid() {

var order = aValidOrder()

.with(aValidOrderItem("book").withPrice(20).build())

.thatIsOpen()

.build();

var repository = mock(Orders.class);

var notifier = mock(Notifier.class);

var checkout = new CheckoutOrder(repository, notifier);

checkout.execute(order);

verify(repository).save(order);

verify(notifier).notify("owner@x.com", orderNumber)

}

This test asserts (using Mockito mocks) that an

order is saved in the repository and a notification is sent out, using

notifier. These are two different expected outcomes.

This test might not look problematic at first. It is however harder to read and more work to figure out what went wrong when it fails. In this case the test name already hints we are covering two aspects.

And suggests there is a test on each side.

Asserting multiple things makes it hard to provide a meaningful name or description.

We prefer to split up this test into two separate tests. A literal split would suggest savesOrder and notifiesOwnerIfPaid, but IfPaid is significant on the left to, so it becomes savesOrderIfPaid.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Preferably, we split them up:

public void savesOrderIfPaid() {

....

verify(repository).save(order);

}

public void notifiesOwnerIfPaid() {

....

verify(notifier).notify("owner@x.com", orderNumber)

}

We make sure our tests run fast, so an extra test won’t affect our feedback loop negatively. Using test data builders like we are doing in the example above helps us keep the setup per test short and explicit.

We have seen worse examples of multiple asserts per test.

Example - All the contains

The following one is taken from WeReview, a conference session management system we have developed. It is written in JavaScript, using Cypress to drive a UI. Have a read through and make a note about the different parts you recognize, and what they could possibly mean.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

describe('Propose a session', () => {

it('given I am administrator, when I create a CFS then I can propose a session, and I can see the submitted session', () => {

cy.visit('/');

login_as_administrator();

const conferenceName = 'cypress test conference - admin login' // 1

const conferenceCode = 'admin2029';

cy.get('#shortCode').type(conferenceCode);

cy.get('#displayName').type(conferenceName);

cy.get('#addEvent').click();

cy.contains('Data updated successfully');

cy.contains(conferenceName).click();

const fields = proposal_fields_one_presenter(conferenceCode); // 2

const text_fields = fields.text_fields;

fill_in_selects_and_text_fields(fields);

cy.contains('Submit').click();

cy.contains('Your session was saved');

cy.visit(`/event/visiblesessions/${conferenceCode}`); // 3

cy.contains(text_fields["session-title"]).click();

cy.contains(text_fields["session-title"]); // 4

cy.contains(text_fields.themes);

cy.contains(text_fields["session-anything-else"]);

cy.contains('Recording Permission');

cy.contains('42'); // session cap

});

});

If this test fails, it will take some effort to find out why it failed. We have to trace the whole scenario up to the failing assert. The test description won’t help us much here. Cypress’s interactive development tooling will help identify the failing test, but it still takes time. And when we run the test in a CI environment, we still have to find the failing line. A wandering test like this hampers the quick feedback loop we crave from our automated tests.

Let’s compare our notes. There are ten instances ofcy.contains, so ten

asserts? But wait, there is more! each ` cy.get and cy.visitare also

assertions. If the target for get is missing, or visiting cy.visit`’s

destination fails, the test fails too. This is a feature in Cypress, and it

should encourage us to focus our test more closely.

We can distinguish four conceptual blocks:

- Given we are administrator, When we create a conference, Then we get a success confirmation and we can navigate to the ‘organise’ page for that conference.

- Given a session idea, When we propose it, Then we get confirmation of successful receipt

- Given I am an administrator, When there is a session proposal, Then I can visit it

- Given I am an administrator, When I visit the session proposal’s page, Then I can see all the values entered by the proposer.

The first block still has two _and_s, but we are making progress. Baby steps.

Naming these parts also suggests tests are less thorough than they could be. Instead of ‘all the values entered by the proposer’ for example, we are checking a sample. ‘All the values’ is significant, because not all roles are allowed to see all the values.

What can we do about this test? As in the first example, we need to split it up in order to get to one (conceptual) assert.

We can apply the Given-When-Then pattern: In this test, each assert is a ‘then’, with a corresponding ‘when’ just before it. We can pull out the then+when into a separate test, and set up the object under test (the Given) in the appropriate state.

What can help against wandering tests

Some things that are helpful against wandering tests are:

- Test data builders

- Extract Method refactorings

Let’s see what one or more extract method refactorings could provide us here.

Wishful thinking

Spitting the test like this is quite a lot of work to do. Let’s take a seemingly simple one, number 2:

Given a session idea, When we propose it, Then we get confirmation of successful receipt

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

describe('When I Propose a session', () => {

// Given remains wishful

it('Then I get get confirmation of success', () => {

const fields = proposal_fields_one_presenter(conferenceCode);

const text_fields = fields.text_fields; // 1

fill_in_selects_and_text_fields(fields);

cy.contains('Submit').click();

cy.contains('Your session was saved');

Now we spot opportunities for better readability. The line marked with // 1 is

redundant for this test. But we can’t refactor that, because we are not on

green. We are missing the Given.

After some discussion, we sketched and executed the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

function given_a_conference({conferenceCode, conferenceName}) {

cy.visit('/');

login_as_administrator();

cy.get('#shortCode').type(conferenceCode);

cy.get('#displayName').type(conferenceName);

cy.get('#addEvent').click();

cy.contains('Data updated successfully');

cy.contains(conferenceName).click();

}

describe('When I Propose a session', () => {

const conferenceName = 'cypress test conference - admin login'

const conferenceCode = 'admin2029';

const given_a_session_idea = proposal_fields_one_presenter;

before(() => {

given_a_conference({conferenceCode, conferenceName});

});

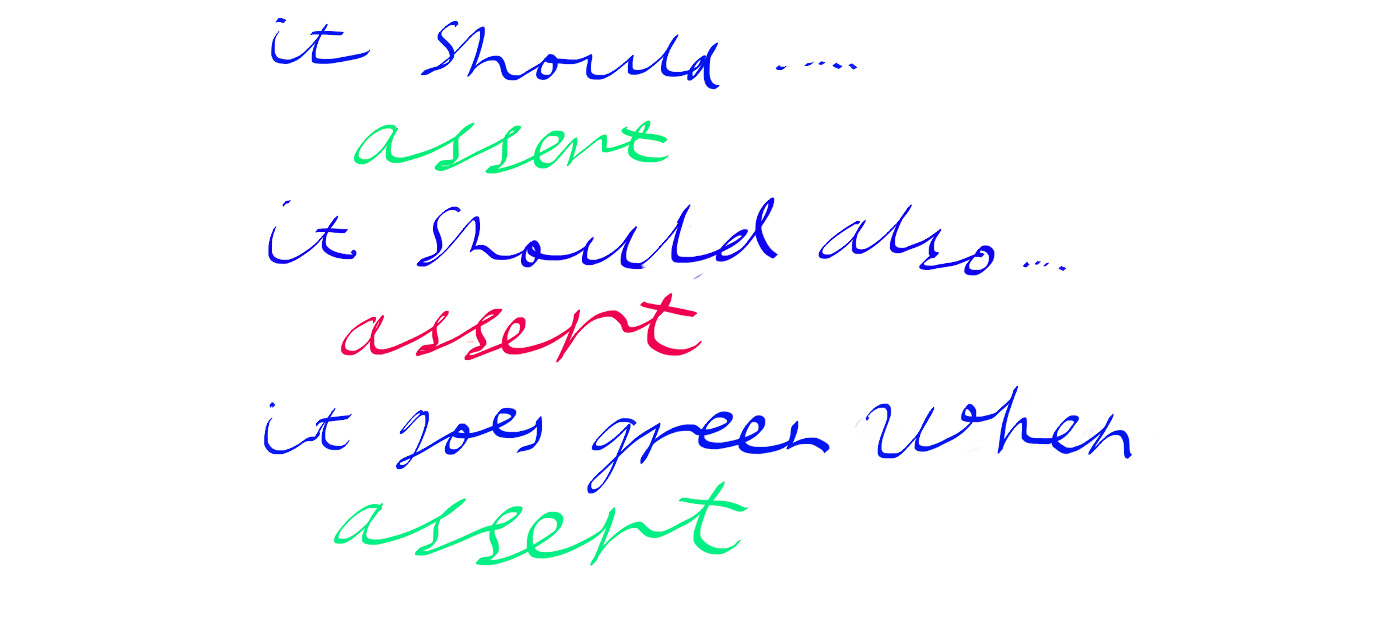

it('Then I get confirmation of success', () => {

const fields = given_a_session_idea(conferenceCode);

fill_in_selects_and_text_fields(fields);

cy.contains('Submit').click();

cy.contains('Your session was saved');

});

});

We found out that the wishful given was a given that we overlooked - we need a

conference. Extracting given_a_conference affords us the opportunity to change

that later, so it makes a conference available without going through the UI.

There was a create_conference function already, but that didn’t quite do what

we need here. Choosing this name also gives us the option to reuse a conference

for multiple tests.

The other thing that jumped out, now there is less code, was that

proposal_fields_one_presenter is an implementation detail. We don’t really

care what is filled in, as long as it is a valid proposal. Having taken a step

back with our four-way split, we ee this can play the role of Given a

session idea.

1

const given_a_session_idea = proposal_fields_one_presenter;

We do a bit of functional programming and assign the detailed function to a

different name in the test’s describe block.

There is still some implementation-ish stuff left, but we believe the test has moved forward in readability.

Effects

Thinking one (conceptual) assert per test helps us in creating short, focused tests that will provide specific feedback when failing.

Focusing on a single assert will help us see code that is doing too much: the issue might not be that the test wants to assert two things, but the fact that the code under test is doing two things. Can/should we refactor the code?

Further reading

The One Assertion Per Test rule was originally coined back in 2004 by eXtreme Programmer Dave Astels (of RSpec fame).

The Given-When-Then way of structuring tests comes from Dan North and Chris Matts, who introduced the concept of Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) in the early 2000s.

The book Formulation, Document examples with Given/When/Then by Seb Rose and Gáspár Nagy goes more in detail on how to write readable Given/When/Then specs.

This is a post in our series on Test Driven Development.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash