Software delivery is knowledge intensive work. We are continuously learning, about the problems we’re solving, about our users and customers, about how we can work more productively. We are building up knowledge in multiple areas, but we are not always good at keeping knowledge or making most use of it. Take working with legacy code for example, which often feels like a process of archaeology, rediscovering long forgotten knowledge.

In this post, we will explore different types of knowledge that play a role in software delivery. This is not intended as a comprehensive overview of everything around knowledge in software development. It is meant as a practical, helpful perspective. This perspective will enable us to develop and keep knowledge more effectively. Knowing which type of knowledge needs which approach will reduce working “against the system”, getting things done more easily and with higher quality.

Knowledge

Knowledge is a broad concept with multiple definitions. There is even a whole field of knowledge management. We will use this working definition based on Wikipedia (as of 24 October 2025):

Knowledge is an awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a practical skill. […]

It often involves the possession of information learned through experience and can be understood as a cognitive success or an epistemic contact with reality, like making a discovery. […]

Knowledge is often understood as a state of an individual person, but it can also refer to a characteristic of a group of people as group knowledge, social knowledge, or collective knowledge. Some social sciences understand knowledge as a broad social phenomenon that is similar to culture.

As practitioners, we focus on what knowledge does for us: knowledge influences behaviour. It includes both factual knowledge and know-how (skills). In software development, we use knowledge to make decisions about architecture, design, code structure, tests, priorities, way of working, etc. Whenever we use the term ‘knowledge’, it also includes skills and know-how.

Software development as knowledge creation

Developing, delivering and operating software is a process of continuously creating knowledge (learning). We are learning:

- about the market, about our users, stakeholders and what is valuable for them;

- new technologies, frameworks, libraries, algorithms, and other solution components;

- how to model our domains properly to get a deep, shared understanding;

- how to create designs and solutions that fit our trade-offs;

- how to work together effectively across different roles and disciplines;

- new practices that can make us more effective (or not);

- how our software products behave in the real world with unforeseen interactions.

We create knowledge through creating a something together. The result of our learning is not just code but a socio-technical system: the code, how it is deployed, documentation, manuals, the development team and its way of working, the organization around the development team that includes product managers, UX, support, management, the community of users. The knowledge we create gets embedded in our heads, in our code, in our organization, in the eco-systems we are part of.

Feedback is key to learning. We learned about fast and early feedback and to amply learning from eXtreme Programming, agile development, DevOps and Lean Software Development.

Taking the perspective of seeing software development as a process of knowledge creation (rather that just creating software applications/services) allows us to manage creation, growing, keeping knowledge explicitly. This is key to becoming a highly productive software delivery organisation.

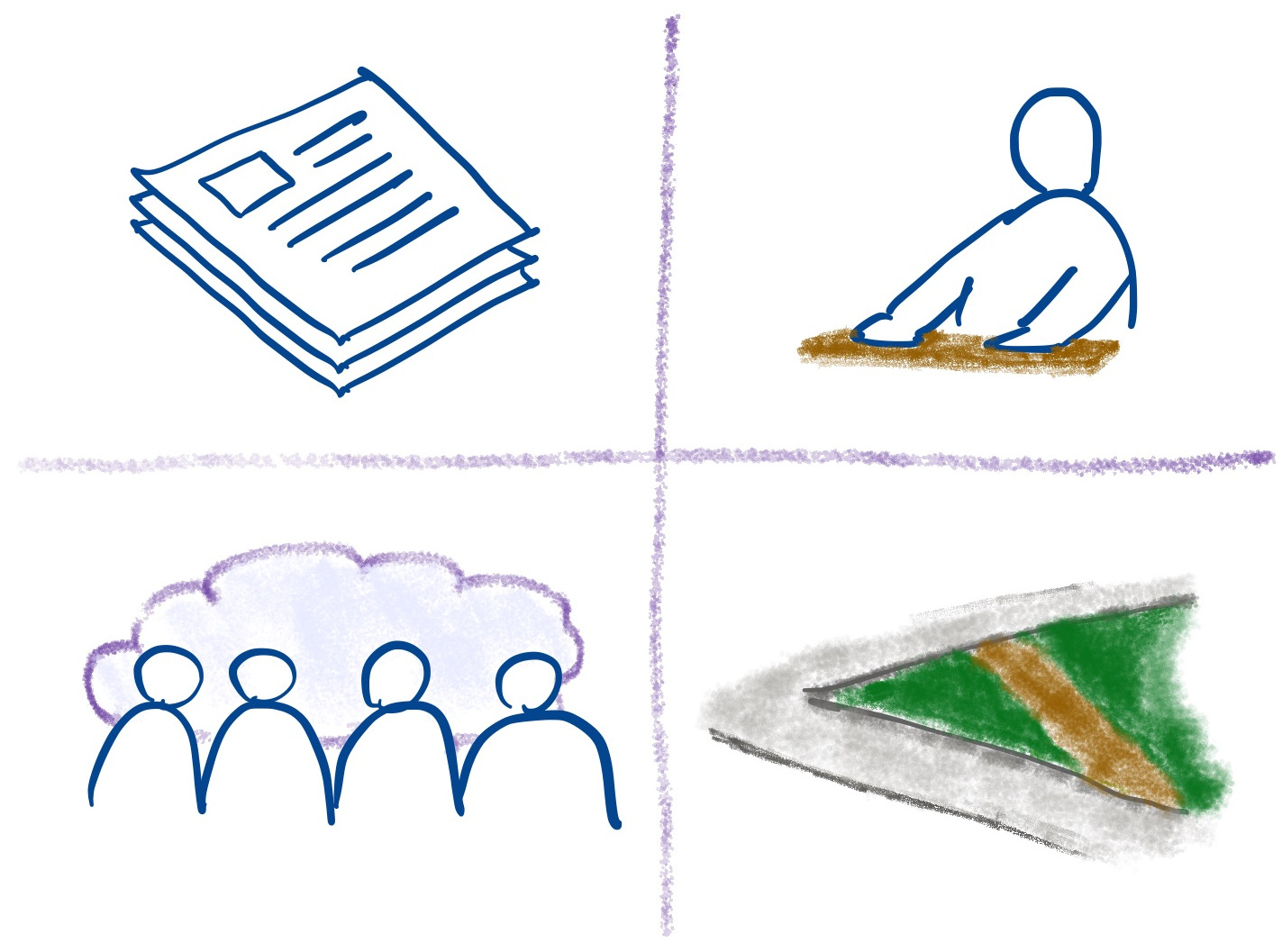

4 types of knowledge - a new perspective

Knowledge plays a pervasive role in our work. but it is also quite elusive. We distinguish four types of knowledge that play an important role in software development. This perspective is by no means comprehensive or complete, but it aims at being useful for growing and keeping knowledge and skills in our organisations:

- Explicit knowledge — things that we can express and codify;

- Tacit knowledge — implicit, embodied, personal know-how that cannot be codified;

- Systemic knowledge — embedded in social systems we are part of, e.g. groups, teams, organisations;

- Stigmergic knowledge — embedded in the physical and virtual environments we work in.

We combine ideas from knowledge management, biology, Cynefin and systems thinking, as well as our experience with software organisations.

Let’s take a look at what these four types mean.

Explicit knowledge - what we can express and codify

Explicit knowledge has been codified, in documents, procedures, manuals, instructions, tutorials, etc. It resides explicitly in artifacts. Explicit knowledge is externalized (not confined in someone’s head) and transferable.

Codify means expressing something explicitly in some (natural, formal, or semi-formal) language and is a broader concept than expressing something in source code.

Code contains explicitly codified knowledge about the domain, about how we solve the problems for our users. It is called ‘code’ for a reason. Domain concepts are for example reflected in classes and functions, comments are telling us what (not) to do. What has often not been made explicit is the rationale of solutions and decisions.

Tacit - embodied knowledge

Tacit knowledge is knowledge that cannot be codified. It encompasses know-how, skills, experience, intuition possessed by people, things which are often hard to express or explain (try explaining how to ride a bicycle for instance). Tacit knowledge is often embodied knowledge - literally fingerspitzengefühl. Because tacit knowledge is not codifiable, we need a different approach to transfer it: we need social and experiential learning, for instance apprenticeships, pari programming, ensemble programming, coding dojos, and other forms of expert guidance.

Development skills are to some extend tacit, so we cannot write down everything a developer knows. We need forms of social and experiential learning within a development team. An example: a pull request review using written feedback is unsuitable to convey know-how from a senior developer to a junior developer. Sitting and working together creates a much better context for effective knowledge transfer: it is social, experiential (learning by doing) and situational (learning what to apply in a specific context).

Systemic knowledge - embedded in social systems

A special form of tacit knowledge is systemic or collective knowledge: knowledge that is embedded in social systems, like a team, department, organization, or any other group of people. Think of group norms, values, taboos, unspoken rules, “the way things are done here”.

These social systems are uniquely determined by their histories - everything that has happened. Systems have collective memory, which influences their members’ behaviour. The whole is more than the sum of its parts: the collective knowledge survives individual members, who come and go over time.

People often call this “culture”, but we don’t find this term helpful. Culture is an emergent property of a social system, formed over time by interactions and events. You cannot “change culture”, you can only influence the events and interactions that will take place, and you’ll have to deal with the systems as it currently manifests itself.

What does this mean for software teams? A team’s systemic knowledge, or “team culture” is explicit or written down. You learn it when you join a team, by immersing yourself in the system. It influences team member’s behaviour and affects decisions a team makes, but often at a subconscious level. It already helps to be aware of this

For example, a team member dismisses a proposal for change saying “we tried this [a very long time ago] and it did not work”. Their belief might be strong even though the world has changed and most assumptions are outdated by now.

Another example: the habit of continuously doing small improvements, in code, tests, way of working, etc is very beneficial, we wrote about that earlier. If it is just an individual developer’s habit, the effect for the whole team is limited, especially if the team norm is delivering features fast. It will cost the developer a lot of energy to stick to their habit - rowing against the stream. When they would leave, there will be no lasting effect on the team. Developing such a habit as a team is more difficult, but also more powerful and longer-lasting.

Systemic knowledge is powerful, in keeping a team together and helping them survive pressure and setbacks. The downside is that it can be more difficult to change things. Systemic knowledge cannot be changed directly - you cannot “change culture” directly.

It helps to learn about a team’s history and any pivotal events that shaped the team. Creating shared experiences can help influence systemic knowledge, adding to a team’s history, for example through story telling, simulations, or games.

Stigmergic knowledge - embedded in our environments

Stigmergy is a concept originally from biology. It is a mechanism of indirect coordination where actors modify their local environment. They leave traces for others to follow. The trace left by an individual action stimulates the performance of a next action by the same or different agent.

We believe that this concept is also useful within software development. The environment software teams work in is not only formed by the physical environment (office space) but also by the code, issue tracking systems, and other tools and artifacts.

Code contain all kinds of signs that influence developers’ behaviour. In a code base that is riddled with null checks, the path of least resistance is adding more null checks. These things act like desire paths. This is not primarily lack of discipline, but actually our brain’s nature wanting preserve energy. Instead of spending brain power on rethinking everything, it takes less energy to follow paths that are already there.

The shape of code and other artifacts influence developers’ behaviour, which can be for bad or good. Every line of code we write can become or reinforce a desire path, so let’s make sure we shape these to guide in a good direction.

Not everything in code and other artifacts is stigmergy. Code also contains explicit knowledge, like domain concepts codified in class and function names, or comments telling what (not) to do. Rules, guidelines, working agreements listed on a wiki are explicit knowledge.If the desire paths in the code differ from what the rules on the wiki state however, the desire paths will usually win.

How does this help us?

Being aware of these different types of knowledge gives us more options to steer a team and the software they develop in a desired direction. It supports looking for ways of less resistance - how to influence team behaviour while putting in limited energy. Some examples:

- Conflicting sources of knowledge — we can write down as a team on how we do things in code (explicit knowledge). This could conflict with desire paths in the code (stigmergic knowledge). There might also be a conflict with how some team members have learned how to do things (tacit knowledge). This makes it more challenging to let the team change its way of working, especially under pressure.

- Resistance to change — what we perceive as “resistance to change” could be tacit, stigmergic and/or systemic knowledge at play, making the system move in a different direction. Good intentions alone are not sufficient. It is helpful to see resistance as information about the system.

- Create on desire paths in code — we can consciously create desire paths and consider how the code we write can influence colleagues (and future us). This can make it easier for the team to make good decisions and is less draining than trying to correct everything afterwards, e.g. in pull request reviews.

- Invest in team skills — to grow team & development skills (tacit knowledge), we need proper investment and proper ways of transferring these skills. We cannot do this through documentation or just reading about it. We need some form of social and experiential learning, through hands-on training, mentoring, working and reflecting together (deliberate practice).

Further reading

- The Principles for managing knowledge are useful to keep in mind, in particular when dealing with tacit or systemic knowledge.

- Ikujiro Nonaka & Hirotaka Takeuchi, The Knowledge Creating Company (1995) and New New Product Development Game (1986); the latter was an important source for Scrum as we know it.

- The Agile Fluency® Model is focused on assessing and growing team skills.

- The ASHEN framework is a method for mapping different types of knowledge in an organisation.

- There is a nice book called Learning Histories by Rik Peters which focuses on organisational culture basically being the resultant of its history (all the events that happened).

- To learn more about seeing resistance as information about a system, see Dale Emery’s Resistance as a Resource.

- We have run some exploratory workshops on stigmergy within a software context, at Agile Cambridge 2023, Lean Agile Scotland 2023, and XP Days Benelux 2023.

Credits

Thanks Willem, Arien Kock, and Patrick Vine for the conversations and sharing of ideas.