We are fans of Test Driven Development (TDD). It has served us well over the years. The TDD cycle - test, fail, run, refactor - is all about getting rich feedback fast, feedback about design decisions, about the test, about your code. We thrive on fast tests. We also want to test-drive our adapter integration and UI tests. These tend to be slow and fragile with low quality feedback, so we try to keep these minimal.

There are some recent developments where slow types of tests have become an order of magnitude faster, for instance testing Vue.js components and Cypress based web end-to-end tests. Karma based tests also come to mind, which are neither unit tests (because they run in a browser) nor end-to-end tests (because they have no back-end). This order of magnitude speed-up changes the whole game, but not only for the better. In this post we will dive into the effects of having fast(er) tests.

Fast Vue.js components tests

Vue components are easy to test using Vue test utils. Even though its API is a bit low level, you can wrap it in your own DSL. These tests run blazingly fast together with the unit tests, in seconds. In the online Agile Fluency® Diagnostic application we are developing, we currently have over 170 UI component tests that run in less that 4 seconds.

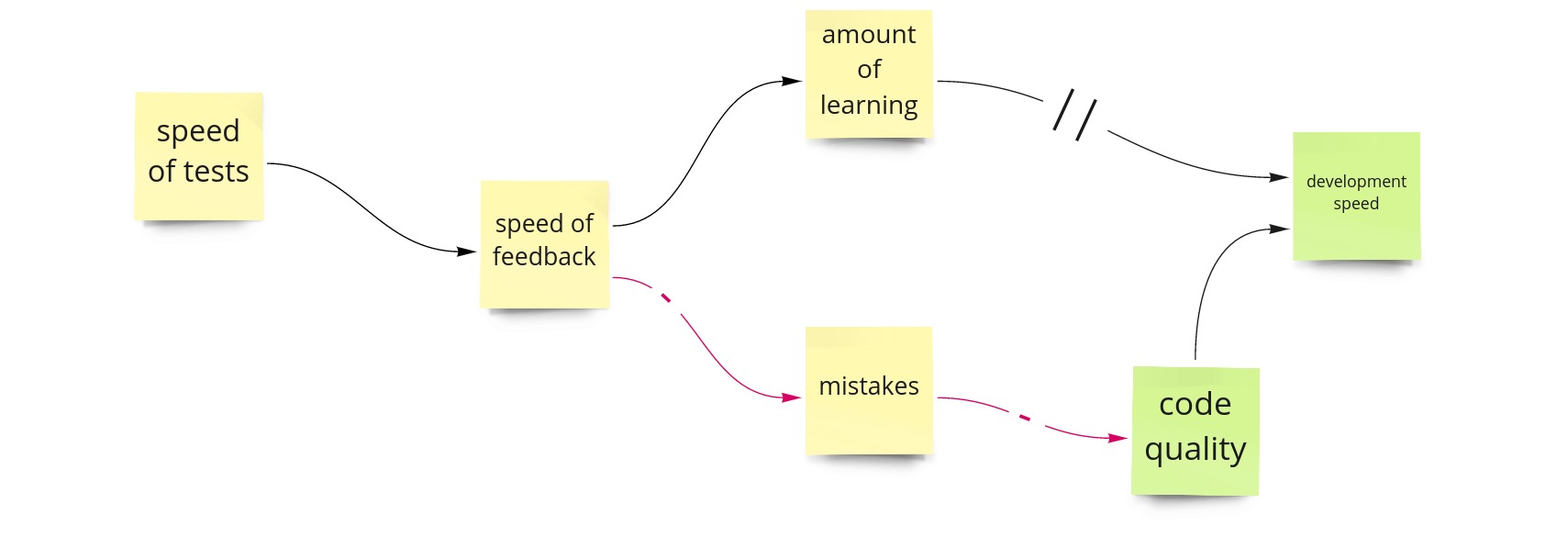

Having fast tests facilitates defect prevention and learning by providing immediate feedback on our actions. This contributes to code quality, product quality and speed of development. In other words, these help your productivity like this diagram of effects shows:

The post-its represent variables - things we can observe or measure. A black arrow indicates an effect in the same direction: if speed of feedback goes up, amount of learning also goes up. A red arrow with a ‘-‘ indicates an opposite effect: the more mistakes we make, the lower the code quality. The || on an arrow means the effect has a delay.

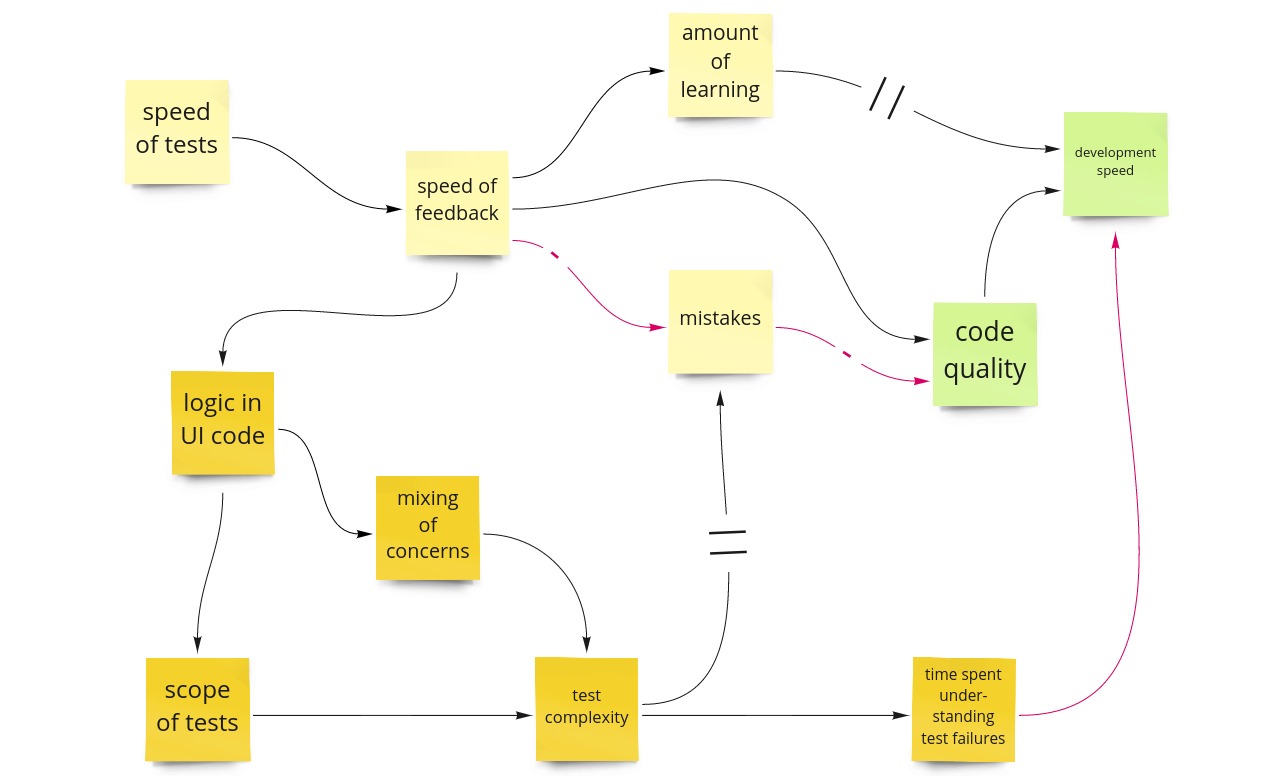

So fast UI tests are great … but they can have unintended consequences and nudge you towards less optimal design decisions.

When testing UI components is difficult and slow, we move the logic out, into classes/functions of their own with their own tests. It is just too much a hassle to test everything in UI component tests. Separating the concerns allows fast tests for most of the code.

Because with Vue.js component tests are so fast, it is tempting to add logic to components and cover the logic in UI component tests. Test slowness is no longer an impediment to prevent this. The consequence is however that we mix UI and logic, and UI components grow more and more complicated. The tests will need to cover all the different concerns, so their scope grows. The wider the scope of a test, the harder the test becomes to understand and the less helpful its feedback will be.

We start losing time on figuring out failing tests. By mixing UI integration and view logic, we start introducing defects because things are getting complicated. There are too many paths to cover in tests and it takes us a long time to understand what the code and tests are doing.

Ultimately, the number of mistakes starts rising, reducing code quality and slowing down development. It starts balancing out the positive effects of fast tests, and we risk becoming less productive eventually.

If we are aware of this, we can consciously decide to put view logic in its own

classes and functions. Even for us the temptation remains, sometimes an innocent

if or a tiny bit of logic creeps into our UI components. This ‘little bit of

code’ acts as an attractor to even more code and complexity starts growing.

Fortunately, we know how to refactor ourselves out of that corner.

We are not saying that Vue component testing is bad. On the contrary, having UI component tests running in milliseconds is great. But it also removes an impediment that prevents us making UI code too complicated. It happens before you know it, but as long as we are aware of this, we can act upon it. So keep listening to your tests.

Fast Cypress end-to-end tests

We see something similar with Cypress, a recent web testing tool that also changes the game by being an order of magnitude faster. We wrote about this earlier. The Cypress developers made different trade-offs than e.g. Selenium/WebDriver, by having the test run in the browser next to the web application code.

Cypress tests run very fast and stable. They provide good quality feedback, for instance by records the DOM state at each step allowing you to see the path that lead to a test failure. This enables us to quickly write UI tests. Cypress facilitates stubbing back-end calls conveniently, so we tend to write component end-to-end tests, with tests having the whole front end component as their scope.

This is very powerful for instance for getting an existing front end under test. If we mostly write end-to-end tests however, we move a way from focused unit and adapter-integration tests. This will not help in keeping our front end code well-structured and loosely coupled, like we described in earlier posts on How to keep Front End complexity in check with Hexagonal Architecture and A Hexagonal Vue.js front-end, by example.

Every component starts simple, but it will grow over time. Covering all the different paths, covering combinations of UI state, view logic, back-end API integration through UI based end-to-end tests becomes cumbersome. Getting high coverage eventually becomes impossible.

As long as we are aware of these effects, we can consciously decide on the test architecture for front end components, and have a suitable mix of unit tests, adapter integration tests and end-to-end tests. Again, we have to be conscious about this, because the slowness of writing and running UI tests is no longer an impediment that keeps us from doing too much in end-to-end tests.

Conclusions

Like Willem said in an earlier post, changing the speed at which something runs by an order of magnitude is a game changer.

As our game changes, we need to stay aware of what other effects the change has. In what directions will our tooling nudge us if we don’t pay enough attention? As long as we make conscious decisions, we can keep playing the game to our advantage.

In UI components, we tend to be strict and move any view logic to its own classes and functions. Keeping concerns separated helps to keep the component’s complexity manageable.

The effects we mentioned are not the fault of Vue.js or Cypress. This post is by no means a critique on the approach these tools take. We are actually quite happy with technology that facilitates rapid feedback! As a developer, it pays to understand the effects of these game changers, so that you can use them to your advantage.

References

A Diagram of Effects is a powerful technique to make sense of what is going on in a team or an organization. We recommend Gerald M. Weinberg’s Quality Software Management series if you’d like to learn more, or read our whitepaper Promise is Debt (PDF).

Credits: thanks to Willem for editing and helping improve this post.