Deciding What To Put Where is half of the work of software development. What should I put where, in such a way that me and my colleagues will be able to find it back later? Finding a good place for things in code greatly helps or hinders maintainability of the code later on.

Knowing what to put where is a skill developed through practice. Things that can be helpful are looking at code through a Hexagonal Architecture lens, making ‘things’ in your code explicit through types or classes, designing with CRC cards, pair programming, and documentation.

Let’s explore this further in this post.

- Knowing What To Put Where

- Adding CSV export

- Internationalization

- Things that help in deciding what to put where

- Learn what to put where

- References

Knowing What To Put Where

An important part of our job as software developers is taking design decisions at all levels: sketching a high level architecture on a whiteboard, where we decide which responsibility goes where; CRC (Class Responsibility Collaborators) design sessions, where we play out scenarios of object interactions, to see which object will have which responsibility; and at the micro-level, like deciding on names for specific operations.

We are not only trying to make the software work for now, we intend to develop in a sustainable way. Therefore we are continuously thinking “what concern should we put where?” We spend much more time navigating, reading and understanding code than writing it. Whenever we need to make changes, we’d like to find out quickly where we should be, and we hope that the concern to be changed is in one and only one place.

Putting things in the right place will help us later on. It is so important that we think it deserves its own acronym: WTPW - What To Put Where

We can put “stuff” just anywhere, but then we will spend many hours looking through the mess. It’s like keeping your shed organized. You can just dump your tools anywhere and figure out how to find the things you need in the future. That saves time now, but is frustrating when you need ‘that thing’. Putting some consideration in what you are going to put where will save you lots of time and frustration later.

How do we decide What To Put Where? We do not have generic rules or best practices, but we do apply numerous design heuristics. It is a skill you learn through (deliberate) practice. So let’s have a look at two examples, to share our considerations about what should be put where. The examples are from our work on the online Agile Fluency® Diagnostic application.

Adding CSV export

In the Online Agile Fluency Diagnostic application, we show a colourful aggregated view of team survey results (the ‘rollup chart’). We decided to make the aggregated data available for download in CSV format (Comma Separated Values), so that our users can process it with their own tools.

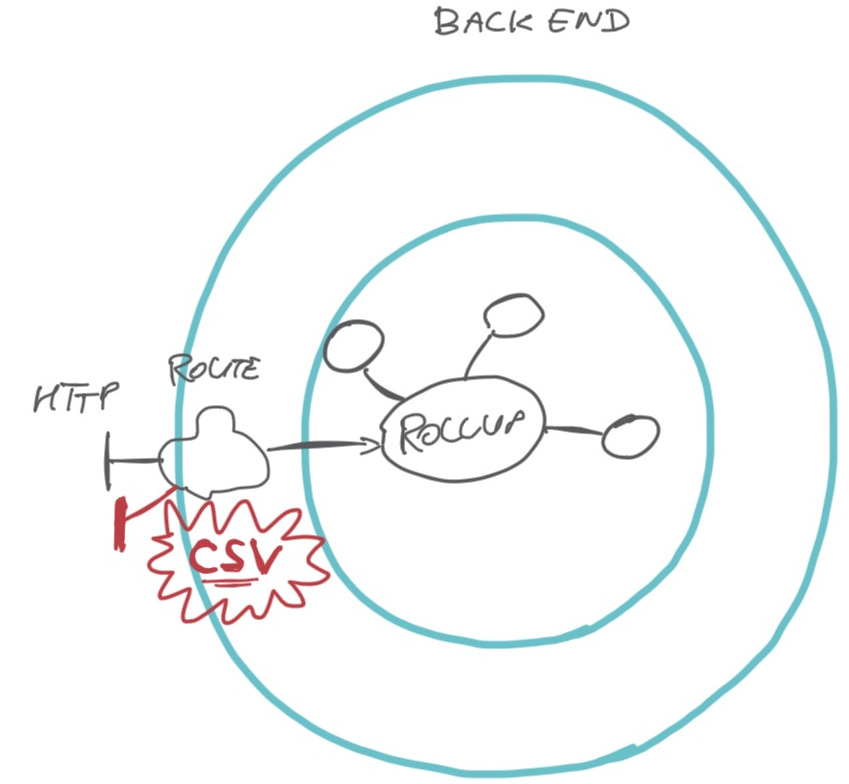

In our back-end component, we already had the following:

- a domain object

Rollupwith logic to aggregate survey data - an HTTP GET route to expose the Rollup data (part of the adapters ring of our component)

- a function that maps the Rollup object to JSON data (in the same module as the route code)

Where do we put a CSV export? We regard it as another view on the Rollup domain object. Looking through the Hexagonal Architecture lens, it does not affect the domain logic, so we do not need any changes there. It is an adapter concern: it is about translating a domain object to a different format on a different endpoint.

We added an endpoint and a function that maps a Rollup object to text lines in

CSV format. A bit of work on the front-end component was required as well, to

add a download button.

As a result, whenever we need to change or add data in the CSV we know exactly where to find it: it is an adapter concern, part of our routing code.

The CSV conversion including headings is currently a single function, 8 lines of Python. Maybe someday, we’d like to have more fancy CSV output, and we might find that ‘CSV’ is a thing of itself. In that case we’ll probably extract a class for it.

Internationalization

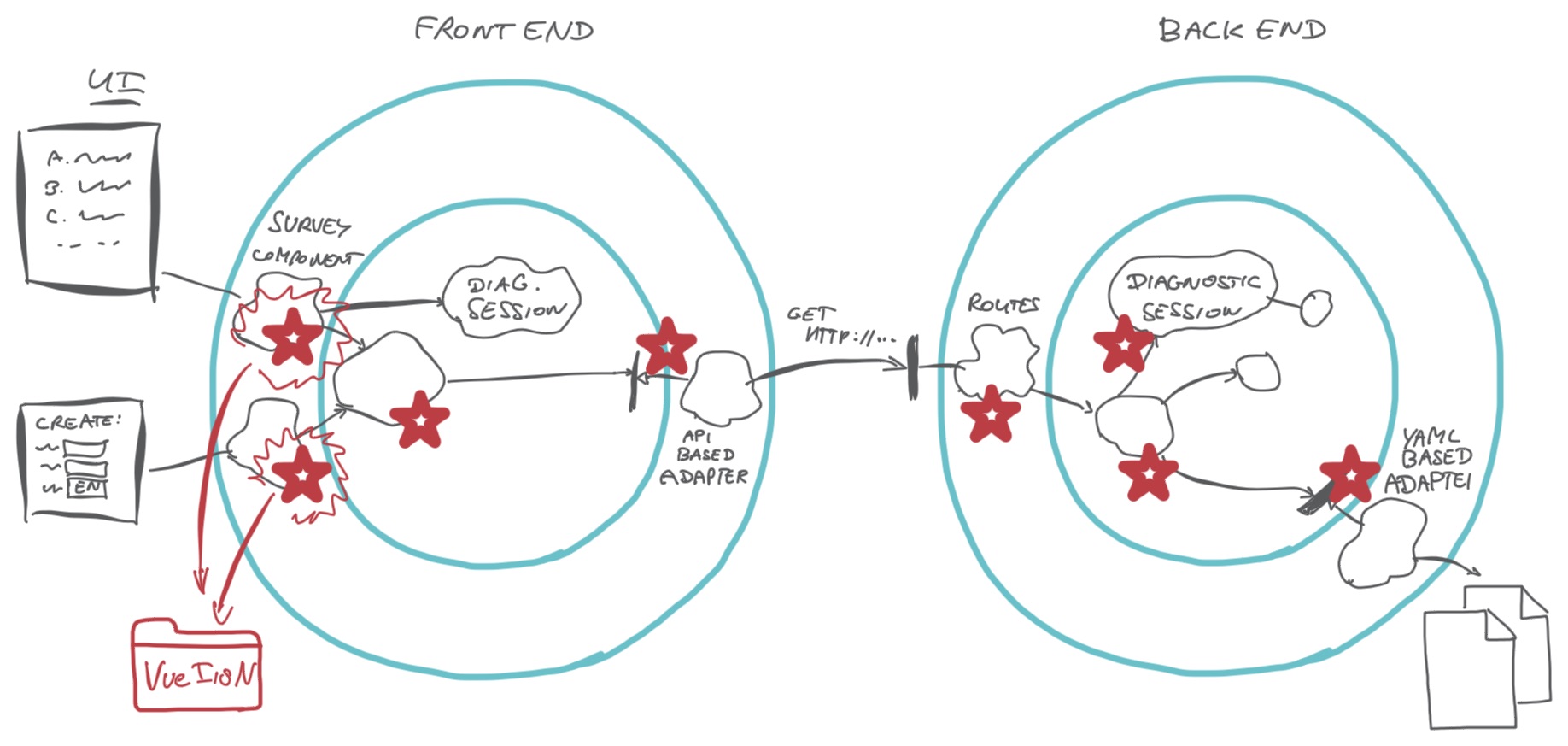

We wanted to offer the Agile Fluency team survey in different languages, where the facilitator selects a specific language for a diagnostic workshop. The original survey is in English, and our colleague facilitators had been working on German and Spanish translations. Having the team survey available in multiple languages makes the online application much wider applicable.

In our Vue.js front-end, we decided to use the

VueI18N library. We created a file with

translations and fed this to VueI18N, which plugs itself into UI components.

It seemed all pretty straightforward and initially, we thought that language and

locale related stuff should be put in the UI components.

The survey contents is not part of the front-end, but comes from the back-end. We extended our back-end with multiple survey translations in YAML format and made the code select the right translation based on the chosen team workshop language.

When creating a diagnostic session, we let the facilitator select a language

from a list of languages. The NewDiagnosticSession UI component (which we

wrote about in an earlier post)

gets the available languages from the back-end.

When the front-end Survey component retrieves a survey, it needs to set its

language to the survey language, so that the accompanying instructions show up

correctly. Some logic around VueI18N started to grow in the Survey UI

component.

Because a facilitator shares the rollup chart view with the team, the rollup chart should also be shown in the correct language. We had to add some conditional logic in a router hook to ensure the current language gets reset when needed.

Hm, it does not smell good…we see more and more knowledge about languages and

VueI18N spread around our code base…

Multiple UI components contain translation logic and depend on the

VueI18N library. Our domain knows about the current language and how VueI18N

works. Our main.js has intimate knowledge about how VueI18N works… We had

code like this in UI components:

1

2

3

this.diagnostic.retrieveQuestions(this.sessionId, this.participantId).then(() => {

this.$i18n.locale = this.diagnostic.language

})

Our UI components start acting as a

Mediator between our domain

code and VueI18N. We followed the Hexagonal Architecture principle of keeping

frameworks outside, preventing VueI18N dependencies in our domain code, but

now our UI components are getting messy.

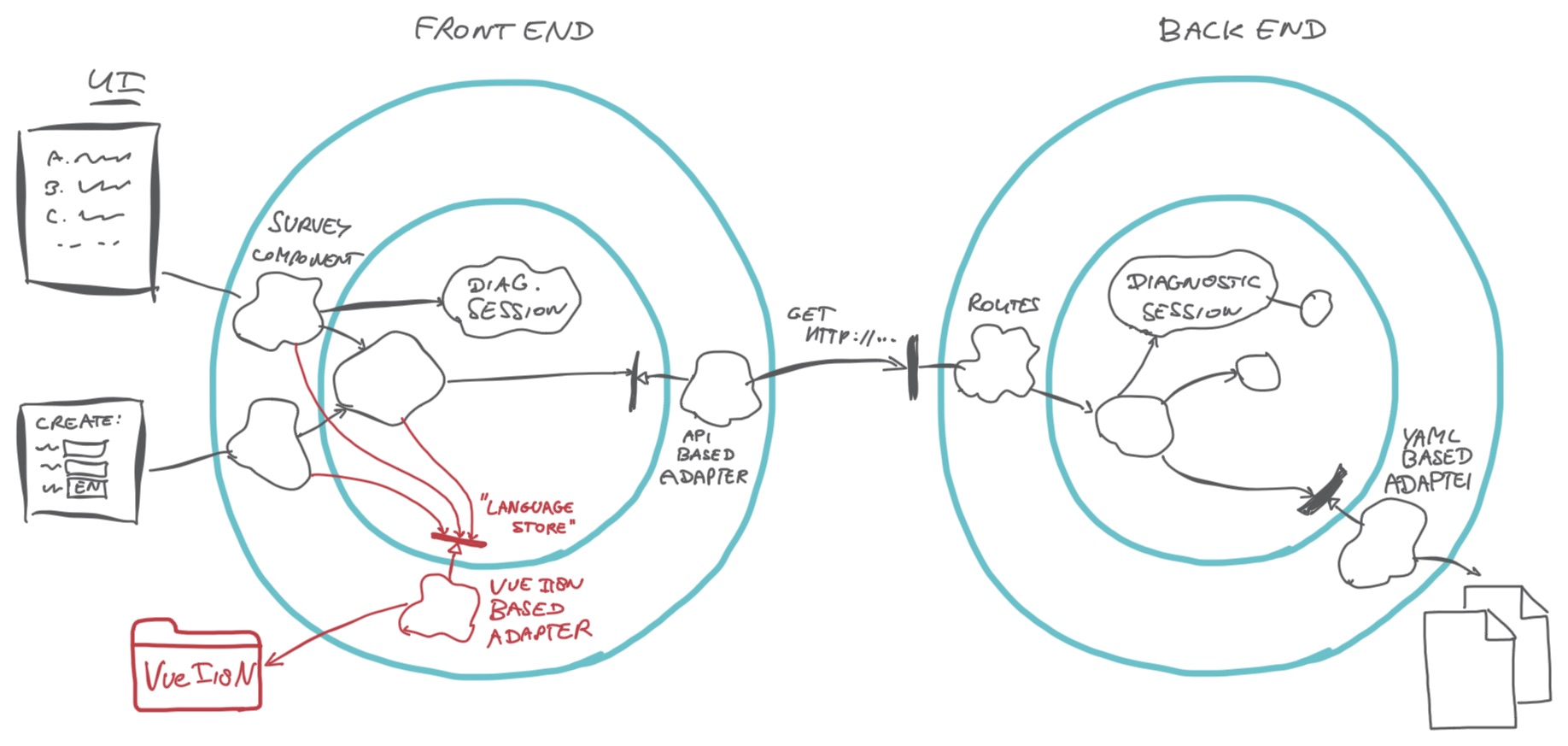

Survey language is a cross cutting concern in this application. We cannot isolate it completely. Both front-end and back-end will have knowledge of survey language.

The question is not how to remove this knowledge as much as possible, but rather how to minimize what each part really needs to know to do its job.

In the back-end, we know the language of a diagnostic session and we select an appropriate survey translation. We also select a translation for invitation emails, but there is no other language-based logic.

Reflecting on what we had created, we realised we missed a domain concept and an

adapter in the front end. VueI18N is closely related to Vue.js based UI

components, but the concept of available languages and a current language is a

concern of its own. Hence we introduced a Language Store concept for this,

which is implemented by a I18nBasedLanguageStore adapter encapsulating

VueI18N dependencies.

Once we had introduced the language store, we suddenly had a place to put all language related stuff: selecting the current language, knowing available languages, resetting the current language. Our domain code can now decide on the language, but it does not need to know how it works out in the UI. The domain code delegates to the Language Store, which handles the details. We have moved the language logic from the UI components to the Language Store.

Once you discover, or uncover, a concept in your code and make it explicit through a type or a class, different concerns start finding their home. Uncovering a concept will make you look in a different way at logic you have been adding in several places.

Things that help in deciding what to put where

- Use Hexagonal Architecture as a lens - Hexagonal Architecture provides a frame of reference to designate different concerns in a system as ports, adapters, or domain logic, and it helps with structuring dependencies.

- Introduce a name for the ‘thing’. We can do this either by design or discovery. Whenever we find ourselves fiddling with for instance a string in several places in the code, this string apparently means something. We look for a good name and create a type for it. Having a thing represented by a name creates a place in the code where related logic and responsibilities want to go. Duplicated code or is usually a strong indicator that there is a ‘thing’ to be discovered.

- Ask ‘Who needs to know what? Can reduce that knowledge?’ The more an object or function knows, the more coupled it is and the more sensitive it is to changes. And the more code we will need to touch if there is a change. In our I18N example, both front-end and back-end know the language of a diagnostic session. Only the front-end needs to know about the current language, the back-end should not care.

- Working with CRC (Class, Responsibilities, Collaborators) cards for rapid design feedback. CRC cards are a lo-fi technique to quickly create a model of objects and their responsibilities on cards. It enables us to play out alternative scenarios and get a feel for how the design works out. It provides good feedback on which object needs to know what.

- Pair programming or ensemble programming - collaboratively doing design, having a good discussion together about what is the nature of the ‘thing’ and where it does belong. Taking time to nitpick about the right place is worthwhile, it will probably save us and our future colleagues many hours of wandering through the code to find the lines to change.

- Test Driven Development As If You Meant It - TDD As If You Meant It is a more extreme form of Test Driven Development, originally proposed by Keith Braithwaite as a workshop technique. With TDD As If You Meant It you let your code grow in the test and only extract a function or class when the code asks for it by showing duplication. This technique turns out to be useful for discovering ‘things’ in legacy code as well. Our tests can be a haven of tiny green fields in a see of brown.

- Documentation helps too, e.g Readme Driven Development or a high level description of what goes where on a wiki. It helps if we have standard places at least for the main concerns, and we stick to that.

Learn what to put where

“How can I learn more about what to put where?” a participant recently asked in our refactoring workshop. There are no best practices or simple lists, it is about skills and design heuristics. So what can you do?

- Practice, lots of practice, deliberate practice.

- Practice together - run frequent team sessions to practice, e.g. in the form of coding dojos or ensemble programming. By putting the code under a magnifying glass and nitpicking together, you will learn a lot, and have a great time!

- Try out alternatives and small experiments, whenever you can. Yes, also when you’re working on production code, when sketching designs on a whiteboard or doing a CRC session.

- Test Driven Development is a discipline of software development that helps in making you continuously think about what to put where. We recommend the Growing Object Oriented Software, Guided by Tests book by Nat Pryce & Steve Freeman.

- Read the 99 Bottles of OOP e-book by Sandi Metz. This book is about learning Test Driven Development and Object Oriented Design, and guides you through different design consideration with concrete examples. Highly recommended!

- Teach yourself the language of Code Smells and Refactorings. Code Smells provide a vocabulary of things that can be improved in code. Mastering this vocabulary will give you a richer perspective on your code. Refactorings provide you a vocabulary of small, well defined design improvements.

- Learn about Connascence. Connascence is a more formal model of different dimensions of coupling in code. It offers a powerful perspective on dependencies - who needs to know what and what else needs to change if I change this?

- Don’t be afraid to make wrong choices. Learning how to refactor away from your previous, not-so-good decisions is much more powerful than trying to learn to do things first time right. The more skilled you get in programming yourself out of corners, the less risky wrong design decisions become and the more you are able to learn, and the more… see the virtuous cycle here?

References

- Buy our Code Smells & Refactoring cards for learning the vocabulary of code smells & refactoring

- Read more about Connascence in Kevin Rutherford’s blog

- More about Deliberate Practice

Credits:

- thanks to Willem for editing and helping improve this post.

- Photo credits: tools photo by Cesar Carlevarino Aragon on Unsplash